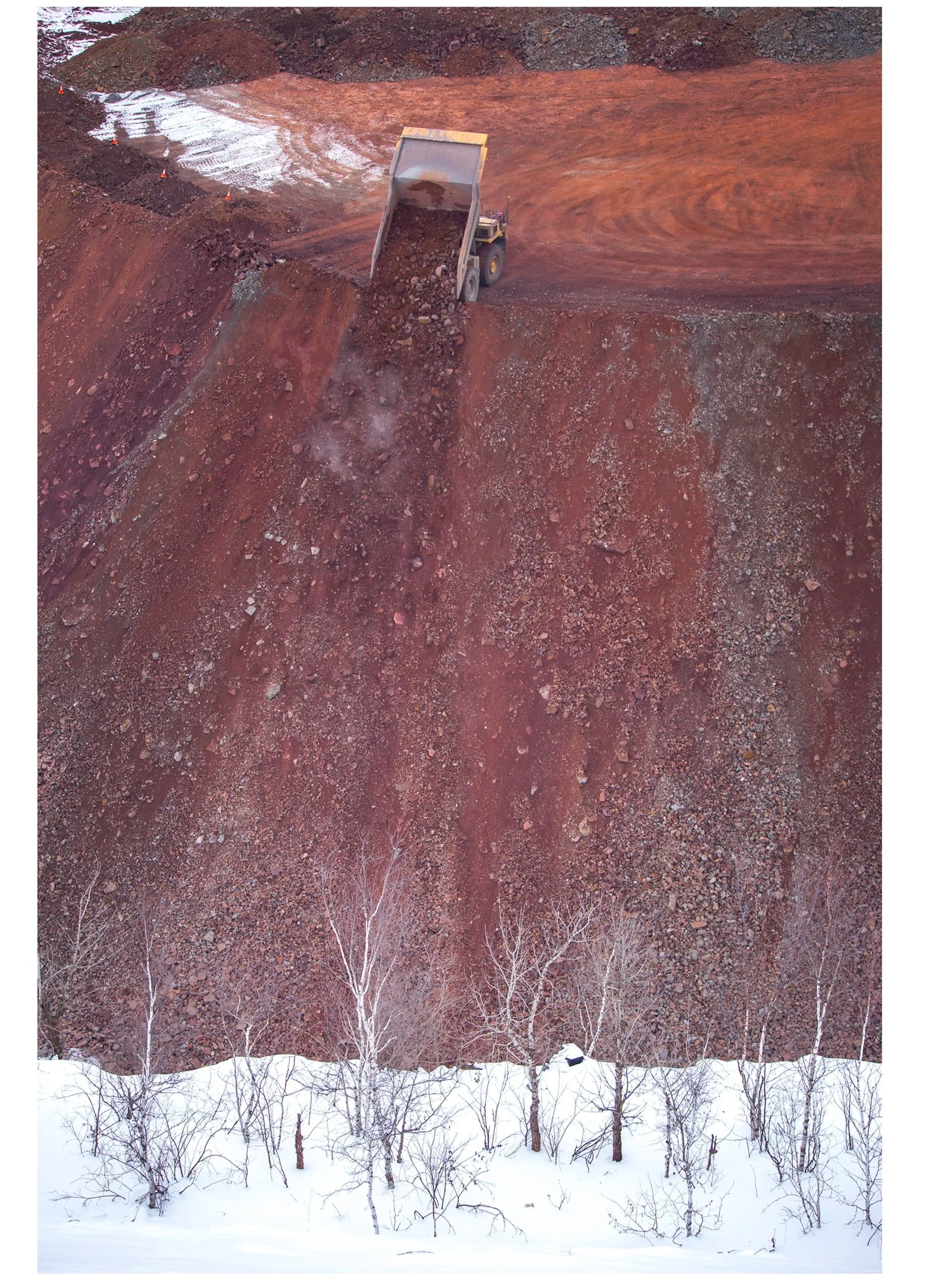

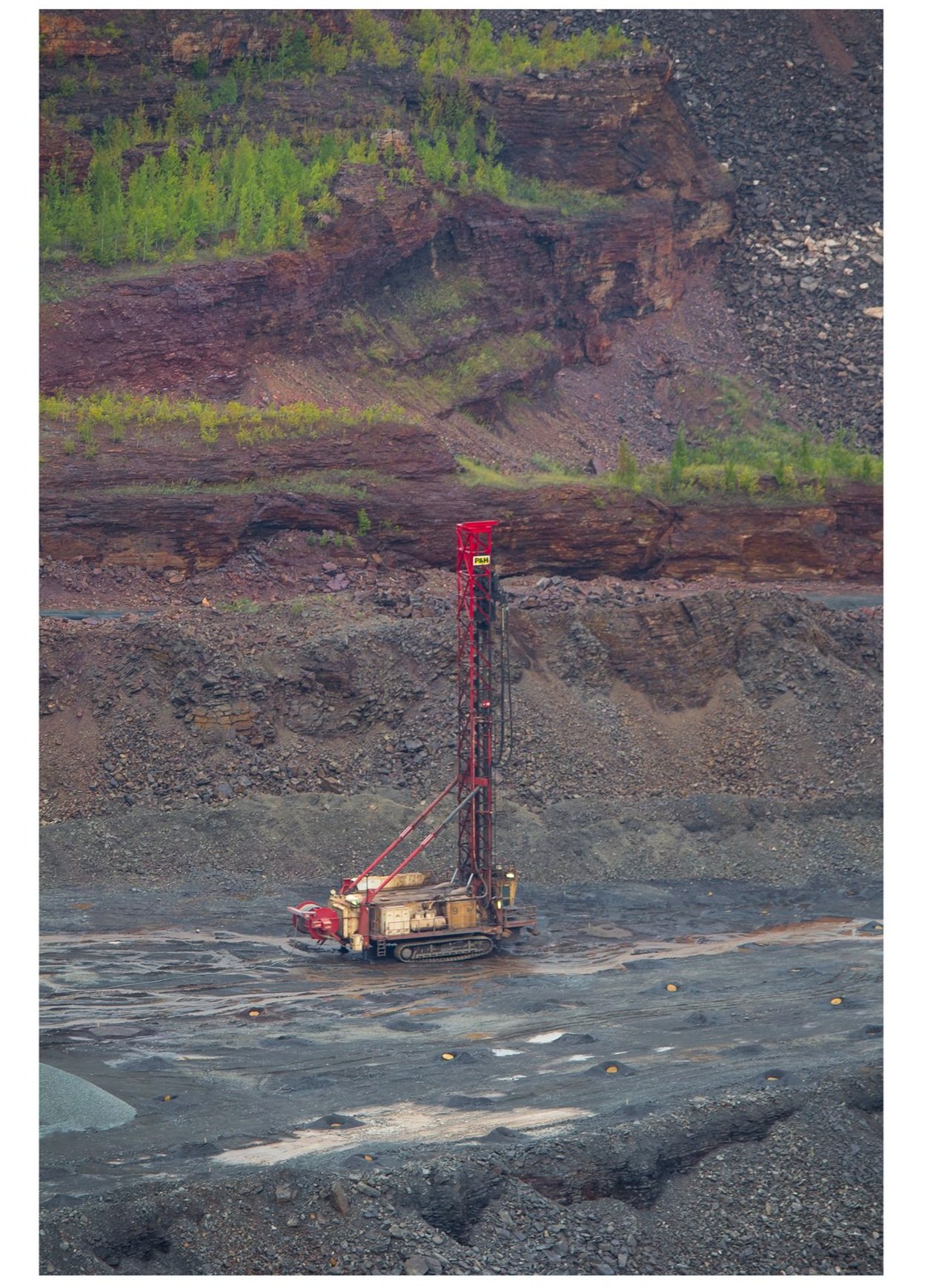

the power of place, 2016

by Adam Jarvi

Digital Print

In a region of the country not associated with dramatic topography, the man-made canyons of the Iron Range have come to define this corner of northern Minnesota. It is a landscape that it is constantly changing due to both the booms and busts of an entire industry. We most obviously associate these pits with active mining, yet they also transform once mining stops. After the high-grade ore was depleted in the post-WWII years, many pits were allowed to fill with water. With no natural outlet, this produced pit lake is several hundred feet deep. At one point, the water seen here in the bottom of the Hull-Rust pit reached the base of the vertical cliff in the upper left corner of the photo. Once Hibbing Taconite has depleted the remaining ore body, pumping will stop, and the water level will rise once again.

Price: $150-$250